The grant will support Chu as she uses radar data and generative AI to map temperatures beneath the Antarctica ice sheet, aiming to improve climate predictions, support coastal planning, and train future scientists through open-access tools and education.

Covering 98% of the continent and spanning more than 5.4 million square miles, the Antarctic ice sheet is the largest single mass on Earth. Georgia Tech’s Winnie Chu is going to map it.

Chu, an assistant professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences has been awarded a $770,000 CAREER grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to create the first-ever comprehensive map of temperatures at the bottom of the ice sheet — a map that will span the entire Antarctic continent.

The NSF Faculty Early Career Development Program is a five-year grant designed to help promising researchers establish a foundation for a lifetime of leadership in their field. Known as CAREER awards, the grants are NSF’s most prestigious funding for early-career faculty.

In total, the Antarctic ice sheet holds enough water to raise global sea levels by over 200 feet — more than 50 feet higher than the top of Tech Tower. Climate models help predict how much of this ice may melt in the coming years, providing critical safety and planning information for coastal communities. However, researchers have limited knowledge of temperatures at the base of the ice sheet — miles beneath the surface — and these temperatures play a critical role in melting.

“Our research addresses this critical gap in Antarctic ice sheet modeling,” Chu explains. “If temperatures at the base are warm enough, the ice can melt and lubricate the interface.” The result? The surface acts like a slip-and-slide, carrying ice toward the ocean and accelerating melt.

“It is crucial that we can accurately predict this behavior,” Chu says. “This map will be an essential step forward in refining our climate models for the safety of coastal communities, for infrastructure planning, and for climate adaptation worldwide.”

Mapping miles-thick ice

The process isn’t as simple as measuring the temperature with a thermometer though. The Antarctic ice sheet is, on average, over a mile thick and can range up to three miles thick.

Chu, who leads the Polar Geophysical Simulation Lab at Georgia Tech, will combine 20 years of radar data — the result of multiple international polar programs — and leverage a technique called “radar sounding,” which analyzes the echoes of airborne radar measurements. The brightness and shape of the echoes can reveal clues about subglacial meltwater and temperatures. To complete the picture, Chu will use cutting-edge generative artificial intelligence (AI) models.

“Innovations in generative AI are part of what makes this research possible,” says Chu, “but the driving force is the data collected by these long-term research studies. AI can help complete the picture — but only because that data exists.”

Preparing for the future

Chu aims for the temperature map to improve the parameterization of climate models and ice sheet projections. This will enable better predictions of future melt and help scientists assess areas that may be particularly vulnerable.

She hopes that the map will drive further advances in polar science. “Our datasets and radar observations will be open access, meaning they’ll be available for all researchers to use,” Chu shares. “We’ll also be sharing the AI processing codes that we develop and the enhanced ice sheet model outputs.”

Additionally, the research will train the next generation of climate scientists through developing educational programs for high schoolers, empowering and engaging students nationwide with hands-on polar science and AI applications.

“This research is about more than just mapping Antarctica — it’s about building tools that help us prepare for the future,” Chu says. “By making our data and models openly available, and by engaging students in the science behind climate change, we’re not only advancing polar research — we’re empowering the next generation to carry it forward.”

Additional Images

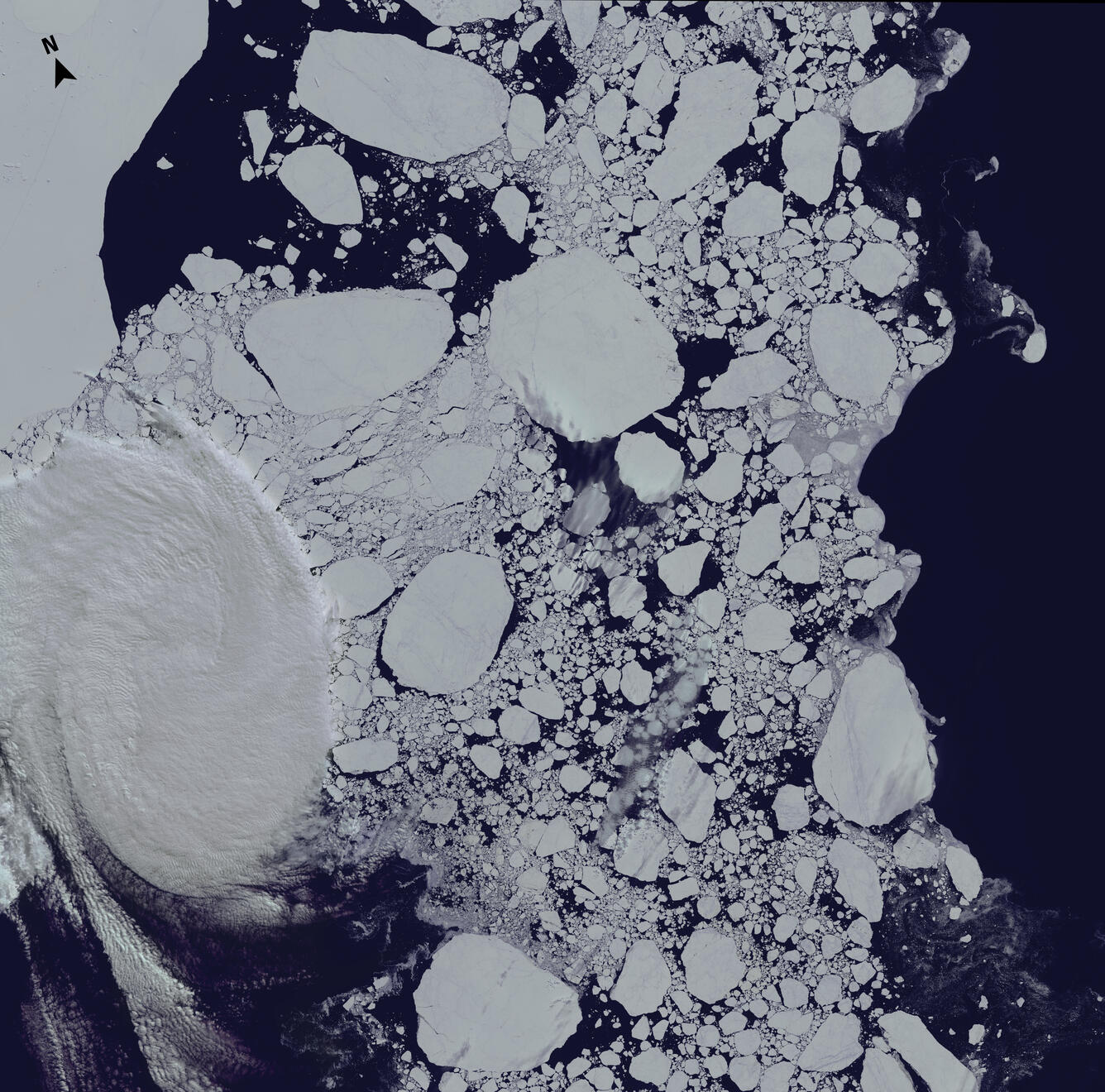

<p>The Ross Archipelago near the McMurdo Station in Antarctica. (Credit: USGS)</p>